Introduction

Violence can occur in many different forms. Traditionally people only consider violence to be physical harm. The defence “I never struck them” when challenged with an accusation of domestic violence does not address the fear the victim had when the perpetrator lifted their hand, harmed the dog, or denied resources to the victim. The occurrence and reoccurrence of fear is the hallmark of domestic violence.

Domestic Violence is a phrase that defines a specific set of violence behaviours that occurs within a family or family like situation. While it can refer to a single incident, it is usually a phrase that implies an on-going situation of cyclic violence, generally from a male perpetrator to a female victim.

Gender

“Australia says no to violence against women”. This is the catch phrase of the new millennium. It is a good catch phrase, as it identifies a problem and a direction. The problem is violence, the direction is against women.

Statistically speaking, women are generally the ones who are the victims and men are the perpetrators, and it is worth acknowledging the dominance of these statistics. However women are not the only victims, and men are not the only perpetrators. Statistics show that men are victimised at a ratio of 1 male victim out of every 3 violent situations [link]. There is a massive paucity of resources to help men. This is not to remove awareness of women who are victimised, or resources from female victims, but to raise awareness of other victims of violence that are not receiving needed aid.

Another area of blindness is in homosexual or polyamorous relationships. Men can be victimised by their male partners; women by their female partners; and one person can either victimise multiple partners, or be victimised by multiple partners. To expect that people are only in heterosexual monogamous relationships denies aid to those in atypical relationships.

The vast majority of the focus of domestic violence is about women specifically because Australia is a male dominated society. The “system” is set up for men and not for women. The focus of violence against women aims to rebalance this domination, and as such, it’s intention is noble. Consider that the average 12 year old male is as strong as the average fully matured adult woman. The strength of the male increases over the following 6 years. This gives the average adult male a significant direct physical strength advantage to average adult females regarding physical violence – the most public face of domestic violence. Hopefully it is clear that a combination of both physical strength and societal dominance places the average female in a far more vulnerable position than the average male. The statistics bear out this vulnerability with the majority of victims (2/3) being female while the majority of the perpetators are male (a bit more than 2/3).

However physical violence is not the only form of domestic violence, and the minority of males who are victims have virtually no support at all. It is important to recognise that males can be victims and also deserve support.

A much better slogan would be – “Australia says no to violence”.

Types of Violence

Violence is about dominating the actions of another through the use of fear, discomfort and hurt. Listed below are a number of different forms of violent behaviour, each with the outcome of behaviour control through direct fear of harm, or indirect fear of loss. These methods are used to either punish undesired behaviour, or to prevent predicted undesired behaviour. All of it is about dominating and control. Perpetrators of domestic violence feel a lack of control over something in their lives and they compensate by trying to dominate their family through violence.

Fear is a key element in domestic violence and is often the most powerful way a perpetrator controls his victim. Fear is created by giving looks or making gestures, possessing weapons (even if they are not used), destroying property, cruelty to pets – or any behaviour which can be used to intimidate and render the victim powerless.

Physical Harm

Direct physical harm of the victim, people (such as children or parents) or animals (pets) the victim cares about. This behaviour can include actions such as pushing, shoving, hitting, slapping, attempted strangulation, hair-pulling, punching etc. and may or may not involve the use of weapons. It could also be threats to destroy or actually destroying prized possessions. It can range from a lack of consideration for the victims physical comfort to causing permanent injury or even death.

Threats

Physical threats such as looming over, shouting, raising a hand or weapon in an intimidating manner, using intimidating body language (angry looks, raised voice), hostile questioning of the victim or reckless driving of vehicle with the victim in the car.

Indirect physical damage such as destruction of property with an implication that it could be the victim, or just general destruction of treasured items, or even throwing wanted items away without consultation.

Stalking before, during and after the relationship can lead to significant levels of intimidation. It may also include harassing the victim at their workplace either by making persistent phone calls or sending text messages or emails, following them to and from work or loitering near their workplace.

Cognitive Abuse / Emotional Abuse

Informing the victim that they are useless, worthless, un-lovable or other undermining tactics that lead the victim to believe they are worthless, a bad person, or no good at something are the underlying factors of cognitive and emotional abuse. Cognitive abuse is using words as weapons to change the way the victim views themselves, or others.

Emotional abuse is more about pushing the victim to have emotions they didn’t deserve such as guilt, shame or sadness. The perpetrator frequently transfers their feelings of guilt, shame and powerlessness to the victim.

This may include screaming, shouting, put-downs, name-calling, swearing, using sarcasm or ridiculing them for their religious beliefs or ethnic background. Verbal abuse may be a precursor to physical violence.

Behaviour that deliberately undermines the victim’s confidence leading them to believe they are stupid or that they are ‘a bad parent’, useless or even to believe they are going crazy or are insane. This type of abuse humiliates, degrades and demeans the victim. The perpetrator may make threats to harm the victim, their friends or family members or to take their children or to commit suicide. The perpetrator may use silence and withdrawal as a means to abuse.

Social Exclusion

Controlling a person’s social connections, such as limiting contact with friends, social groups, church etc.

This involves isolating the victim from their social networks and supports either by preventing them from having contact with their family or friends or by verbally or physically abusing them in public or in front of others. It may involve continually putting friends and family down so they are slowly disconnected from their support network.

Denial of Affection

Refusing affection that would normally be given to assert dominance. This often looks like the cold shoulder, and should not be mistaken for the person taking time to process, or needing time to recover from a negative interaction.

Financial Control

Denying funds for reasonable items, such as clothing, outings, presents to family, health etc.

The perpetrator takes full control of all the finances, spending and decisions about money so the victim is financially dependent on their partner. Also denying the victim access to money, including their own, and forcing them and their children to live on inadequate resources and demanding they account for every cent spent. This type of abuse is often a contributing factor for the victim becoming ‘trapped’ in violent relationships.

Sexual Abuse

Any unwanted sexual behaviours. Rape in marriage is possible and happens. This includes forcing the victim to have sex when they aren’t in the mood, or with other people. Any non-consensual or threat based coercsion combined with sex is bad. If it is bad for you to do it to an unconsenting person, then being in a relationship and forcing them to do it beyond their consent is also bad.

Aggravated assault / Homicide

A primary driver of domestic violence is the perpetrator feeling powerless and attempting to dominate to reassert their feelings of control. When a partner attempts to leave, or assert themselves, the perpetrator will perceive this as a loss of their control and frequently escalate violence to reassert their feelings of control. This can lead to aggravated assault or even domestic homicide.

Spiritual Abuse

Denying a person their spiritual beliefs.

This includes ridiculing or putting down their beliefs and culture, preventing them from belonging to or taking part in a group that is important to their spiritual beliefs or practising their religion.

Separation violence

Often after the relationship has ended violence may continue. This can be a very dangerous time for the victim because the perpetrator may perceive a loss of control over the victim and may become more unpredictable. During and after separation is often a time when violence will escalate leaving the victim more unsafe than within the violence of home.

Women’s shelters exist to help support recently separated women, however many of these places are known to violent men. So far as I can determine, there are no men’s shelters.

Victims usually seek shelter at friends and families. Perpetrators usually try to minimise social contact to minimise the help that friends can give for this very reason. Perpetrators are likely to go to friends and family, to try convince the victim that they are sorry, that things will be better and to reconnect the relationship. The perpetrator can be incredibly charming.

If this charm fails to work, the perpetrator can turn to violence behaviour, escalating as they feel their power and control over the relationship slipping. This can begin with threats, damage to property, harm to friends, family and pets, charming and sleeping with friends, creating problems at work, direct physical assault and potentially ending in murder. This chain of violence is intended to force the victim to come back home to stop the escalation.

Cycle of Violence

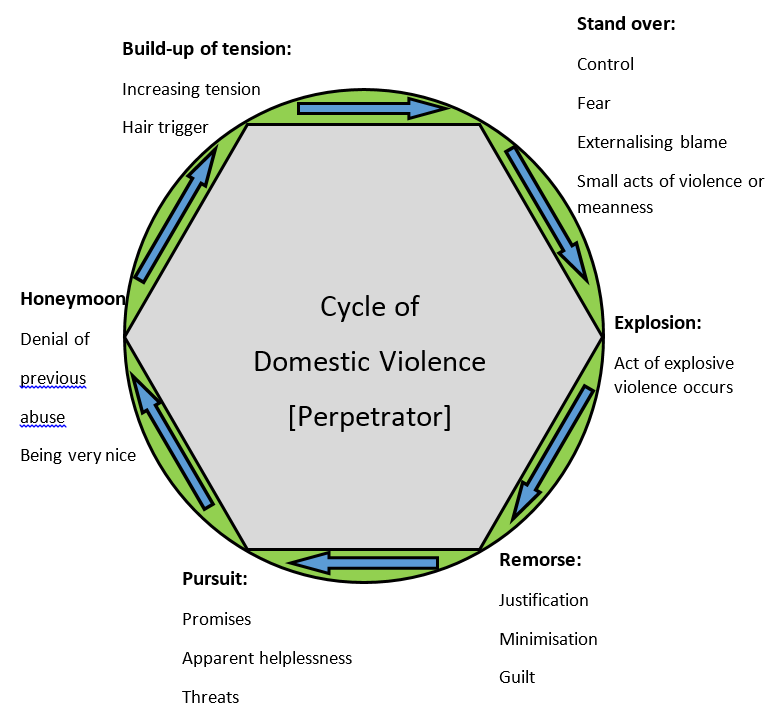

When violence is on-going, it falls into a rhythm and metre. This will start to evolve into a cycle that is very predictable. At each stage the violence can stop, however if not addressed, then the cycle will continue. There are two layers to the cycle, the perpetrators and the victims.

Perpetrators Perspective

Domestic Violence – Perpetrator’s Cycle

Explosion

The final act that creates a recognition of wrongness. While this is frequently an act of physical violence, it can be any forms of the violence listed above. This explosion is the straw that breaks the camel’s back and creates the recognition that this was too far, wrong or needs to change.

Remorse

While the title is remorse, not all perpetrators state feeling remorse. By their actions you may know them, such as trying to justify their explosion and the events leading up to the explosion, minimising the impact of the straw that broke the camel’s back, or by either stating guilt or implying that the victim should feel guilty.

Pursuit

Once the explosion has been justified and minimised, it is time to pursue the victim to reconnect the relationship. When the victim tries to evade reconnecting, this can lead to stalking. The perpetrator will make lots of promises of better behaviour, and try to give the appearance of helplessness in this cycle with phrases like “I couldn’t help it”, or “there’s nothing I can do”.

Honeymoon

Once the victim has agreed to re-join the perpetrator, lots of effort is put in by both parties to make everything wonderful again. There is a general denial of previous abuse, forgiveness of previous abuse and extra efforts to be nice. This honeymoon period is what the victim usually looks back on fondly when they say “but I love them”, yet this is only a small portion of the relationship.

Build-up of Tension

The extra effort put into the honeymoon period begins to wear off and tension begins to build. Irritating behaviours begin to build, forgiveness begins to drop off and the recognition of an upcoming explosion begins to settle in.

Stand Over

The stage before the explosion is full of controlling actions which lead to fear. The perpetrator externalises their inadequacies by blaming the victim. Small acts of violence or meanness appear, showing the true nature of the relationship. Eventually this bubbles over into an act that crosses the line, which is the explosion listed above.

Victims Perspective

Explosion

The final act that creates a recognition of wrongness. While this is frequently an act of physical violence, it can be any forms of the violence listed above. This explosion is the straw that breaks the camel’s back and creates the recognition that this was too far, wrong or needs to change.

Avoidance

The victim is shocked, surprised and hurt from the explosion and needs time to comprehend the hurt associated with the violence. The victim feels betrayed and is likely to being making statements along the lines of “never again”, or “why did I let this happen”. The victim avoids the perpetrator, perhaps moving out temporarily, locking oneself inside a room, or having the police remove the perpetrator.

Hunted / Wanted

The victim is hunted by the perpetrator, who needs to reconnect after having gone too far. The victim may feel hunted if trying to escape the relationship, or wanted if not committed to leaving the relationship. The perpetrators pursuit can seem romantic, and the apparent helplessness of the perpetrator can make the victim feel empowered. Unfortunately most promises are generally short lived.

Honeymoon

The victim has accepted the perpetrator back into their lives, often with terms and conditions. The perpetrator is initially meeting these terms and conditions, paying plenty of positive attention and doing all the things that were promised. Life seems wonderful and the way it should be again. The victim will reminisce on previous visits to this part of the cycle and may delude themselves into thinking that this is how it always is. Unfortunately it isn’t, hence the cycle. The victim has also made promises and is managing to stick to these, often taking on greater responsibility for the violence in the system than is fair.

Build-up of Tension

The perpetrator is no longer able to maintain the effort required to maintain the fiction of the honeymoon period and the mask begins to slip. The victim is also no longer able to maintain their part of the play. Tension begins to build and the victim begins to look for signs of violence and starts to consider their exit strategies.

Eggshells

The victim is hypervigilant for signs of impending violence. The freedom’s won in the honeymoon phase are evaporating as the controls are clamping down from the perpetrator. More and more of the perpetrators lack of inner control is being blamed on the victim and the victim is walking on eggshells to avoid triggering the explosion. Frequently the experienced victim will purposefully trigger the explosion at a time of their choosing, just to get it over with and to minimise the size of the explosion. The frequent excuses for this are “better a black eye than a broken arm”, or “I just could bare the uncertainty anymore”. Unfortunately this exercise in victim control over the violence only restarts the cycle rather than stopping it.

Which brings us back to the explosion phase above.

Exiting the Cycle of Violence

The most common point of exit for the cycle of violence is after an aggressive explosion. Once an explosion has happened both the victim and the perpetrator tend to look at what they have been through. This time of review can be viewed as an experience to not go through again, or relief that it is over and an attempt to get back to the good side of the cycle. The “not do this again” , or a recognition that this is yet another loop of the cycle is an exit point.

This isn’t the only point where you can exit the cycle of violence. Any part of the cycle can be a point of exit, other parts are just not as common.

Exiting the cycle of violence can be separation of victim and perpetrator or staying together and working on the factors of violence and control.

Once the cycle has been disrupted, the emphasis is on learning how to live in harmony. It is vitally important both parties recognise their parts in the cycle and how both parties, working together, can dismantle the cycle of violence, even if separation from each other is the wisest path forwards.

Staying Together

The default answer of most people asked in a domestically violent relationship is to stay together. This can be due to a host of reasons, such as fear of consequences, over valuing the “good side” of the cycle, an over estimation of the value of love within the relationship, old fashioned “till death do us part” values, concern for any children within the relationship etc.

The challenges for people staying together is avoiding bringing the habits of history back into the present. Both the perpetrator and the victim have a role to play in dismantling the cycle of violence. The perpetrator needs to identify their strengths and weakness and find ways to use their strength and address their weakness; understand their anger and find non aggressive ways to address that; relearn to respect their partner; to learn how to communicate to their partner in an effective way and identifying the key aspects of what is good in the relationship and using that as a focus for forming the new relationship of harmony. The victim needs to identify what their own strengths and weaknesses are; how to manage their anxiety of impending explosion; the key aspects of what is good in the relationship and better means of communication.

All parties need to find safe words to indicate upcoming concern / fear / need before the emotions become an imperative (a requirement to react, vs a desire to act), a means of safely taking time and space from each other without suspicion, and to identify what it means to be a concrete functioning family again.

Separating

Frequently the best option is to separate. Concluding a separation usually follows either an extreme explosion that has crossed too many lines, a history that seems to be unforgivable, failed attempts to break the cycle of violence, or a recognition that even if the violence were to be gone, the trust is now lost and can never return.

Separating is hard. It is rare that assets are divided evenly, that support is mutual and space is respected. Usually the separation is more of the slash and burn, salting the earth behind you style of separation. The perpetrator can shift to stalking mode, or become a hunter with a real potential of aggravated assault or murder. Collateral damage can occur to objects, friends and pets. The danger is real, but should not stop the victim from separating if necessary. For fear of safety, some victims have changed state or even country, changing their name, left behind all family and started from the very beginning again. This is about almost as rare as the mutual separation, but the risk is significantly higher.

Mutual children can complicate separation. All parents have a technical default right of visitation. To change this requires evidence, court support or hiding.

Extended families can be unsupportive if they hold to old fashioned values or have a culture of gendered domination, or if they have been fooled by the charm and charisma of the perpetrator. Extended families can also be a point of vulnerability to the perpetrator.

To exit might require cutting off large portions of family.

Once separation has been successful it is important for both the perpetrator and victim to begin looking at their relationship pattern and recognise the power they have to avoid a cycle of domestic violence in their next relationships.

Learning How to Live in Harmony

Whether a family stays together or separates, living in harmony is an important goal. Frequently separated people look for a new partner that has similar qualities to their last partner, or bring the habits of a cycle of domestic violence into a new relationship with the result that their new relationship becomes violent too. Frequently families that stay together bring back old habits in times of stress and cycle back into violence.

To change the nature of the relationship, each person must make changes. While neither has the strength to change the nature of an existing relationship on their own, both together can do so, and either can corrupt a new relationship with violence.

A Victim of Anxiety

This is a touchy subject. While the victim may not want violence, without an occurrence of expected violence their anxiety can increase to the point where they goad their partner into violence just to get it done. The victim can be wondering when the explosion is going to take place. The longer the explosion takes to arrive, the greater the fear of an enormous explosion becomes. Imagine a balloon being filled up with air. You know that at some point it must burst, but you don’t know how big the balloons capacity is. If it only has a small capacity, the explosion won’t be too loud and scary, and may seem quite manageable, yet it means the balloon will pop in only a small amount of time. If the balloon is a regular sized balloon, the explosion will take longer to simmer but will be quite loud and scary. If the balloon is huge, then the end explosion will be massive and the anticipation along the way will be awful. This is how the anxiety behind anticipating the cycle of domestic violence can goad the victim to pop the balloon early, just to trigger the explosion when it isn’t so big and scary. It gives the victim a feeling of power over the inevitable explosion, allowing the victim to approximately time the explosion to their convenience and scale.

The victim’s partner is not necessarily a balloon though. There may be an escape valve that means when the pressure builds to dangerous levels, the vessel releases pressure in a safe and harmless way. This is how most people work. The problem is, for the sake of personal safety and probably limited exposure, the victim views all partners as perpetrators and keeps waiting for the inevitable bang. The perpetrator may have learned the skills to install a safety valve, but never get to a point of using it successfully as the fear of the victim prematurely triggers a rupture before the safety valve can be used, or the safety valve has been used a few times, but the victim does not see this, so thinks the balloon must be truly massive by now… A new partner may have all the safety valves in place to regulate their aggression, but if the former victim has not addressed their anxiety, then they will groom the new partner into a cycle of violence in order to address the anxiety.

Some may read this and be angry that I have stated that the victim brings it on themselves. This is NOT what I am stating. I am attempting to explain the mechanism of anxiety and habit and the risk that creates in prolonging a cycle of existing violence, or corrupting a new relationship into such a cycle. There is no excuse for the perpetrator to lose their temper and commit an act of aggression. Ever.

Perpetrating Aggression

The perpetrator’s primary failings are around power and aggression. Fundamentally the perpetrator feels they have lost power in some area of their life, which triggers the warning emotion of anger. Either the perpetrator cannot address this loss of power directly, or is unaware of it’s consequence. The anger builds and the perpetrator does not know how to peacefully deal with this emotion. Aggression is used to reassert power, but only achieves a brief respite in their feelings. The aggression is an act of violence against those who do not deserve it, the innocent family. Because the initial loss of power hasn’t been rectified, the anger builds again and the aggression is used again to create a momentary and temporary correction to the feelings of internal power with the consequence of family harm.

Let’s look at the three different parts of this. The loss of power, the warning anger and the rebalancing aggression.

Each of us lives in a world of action and reaction, of cause and consequence. When we make decisions and then actions, we change the environment around us. This exercises our direct power on the world. If we act and no change occurs, we feel like the action was a waste, that there was no power in it. If the action has only a partial success, we can see the effect of our action, but feel like it wasn’t enough. If we can lift a finger and create a huge effect, we can feel very powerful. This is a direct example of power.

Indirect power can be just as fulfilling. Indirect power is the perception of how we are viewed by others. Consider when you were at school. Your teacher gave you an instruction and you did it because they were in authority over you. When you didn’t, they either raised their voice, gave you a poor mark or told you to go to the principle. If you ignored their raised voice, didn’t care about the poor mark and just left school when you got out of the classroom instead of going to the principle, the teacher has no power over you. The teacher is going to become very frustrated because they can’t create the change their action was supposed to do. Indirect power is full of assumptions. You act as the teacher bids because you fear the consequences, or you just think it is the right thing to do. You respect your boss because they are a nice person, can fire you, or can give you a pay rise. You believe your gender is superior and should be respected by the other gender, or that children should respect you because you are older, that you can tell older people what to do because you are in your prime and they are passed it and so on. So long as the world reacts to your actions as you expect, your assumptions are secure.

When the world does not act as you expect, or a situation changes and the extent of your ability to effect the world around you changes to become less, you can feel less powerful. This could be a work situation where you are demoted, or put into a precarious work situation; your friends pecking order has changed and you are now at the bottom; a diagnosis of some nasty ailment has been handed to you; your position in the relationship has changed; or some other situation occurs where you are not in a good position.

When your power changes, the emotion that warns you of this is anger. Anger is a fundamental emotion all humans across all cultures feel. Anger is an emotion written about in both some of our earliest texts and in our modern books. Fundamentally it informs you of when a boundary has been crossed that increases your danger or lessens your ability to act. We do not become angry when an event occurs that increases our ability, only when it is perceived to lessen our ability to act on the world around us. When we feel that there is nothing we can do to address the thing that is lessening our power, we can become very frustrated and seek to redress this power loss by gaining greater power over something or someone else. We can transfer the anger we feel from one thing into another thing, either by amplifying a petty anger or frustration, or by distorting what we perceive to justify the anger we feel. For example, the perpetrator may be frustrated by a loved one’s illness, or having been made a fool of at work, they can’t address this directly, so instead targets their partner. The partner may have done a mostly innocuous thing for years, such as stacking the forks on the left of the draw and the knives on the right, but this is no longer acceptable and a fight breaks out over the order of the cutlery. Another example of transferred anger could be suspicion that the partner is cheating on the perpetrator. The perpetrator now begins to see lots of signs and signals of cheating, even though it is completely an hallucination. There is no evidence because there is no cheating.

Aggression is a tool humans use to fend off an attacker. Consider the iconic attack of the cave koala, coming out to eat you. You try to look bigger and scarier, yelling, screaming and making noise. If it keeps coming, you strike at it, trying to drive it back. Fear is the emotion you wish to instil in killer koala so that it no longer wishes to attack you. These are the same tactics humans use on each other to gain dominance and power. While this is a primal method of balancing power in an attack situation, it is mostly useless when dealing with a social situation, or when not able to directly address the perceived attacker or unknown threat (when the source person who is diminishing the perpetrators power is known, or if the source situation is unknown).

To identify when aggression and control are unbalancing a relationship, it is important to identify if the aggression is addressing an actual threat, and if the control is actually improving the situation. Both of these actions are creating a momentary salve of comfort for the perpetrator, but if they don’t actually change the situation of power imbalance, they are useless and should be discarded as soon as possible.

To break this cycle of violence, the perpetrator must look at their own emotions and learn how to recognise what they are feeling. Head over to the section on Basic Emotions (Workbook) to learn more about this. They need to learn to separate the emotion and the reaction so that you can insert thought. This changes event -> emotion -> reaction into event -> emotion -> thought -> action. Also learn to identify the source of the power problems, whether it is a cultural misperception, an event that has occurred or a person who is in conflict. Take steps to address that problem and learn to not take out frustration on their family. If habits are ingrained, then the perpetrator may need to consider separation until they can retrain themselves and either rejoin their partner, or find a new partner.